Consciousness: a primer

This is the introduction to consciousness I wish I’d had when I first got curious about the topic. Avoiding complicated philosophical terms, I’ll describe what we mean by consciousness, present the different problems and theories, etc.

Hope it can help others as well!

What consciousness is (and isn’t)

Simply, consciousness is the fact of having an experience. There is something it feels like to be you right now. That’s the whole definition.

But because people still get confused by this definition, let’s clear some of this up:

You’re conscious when you’re asleep. Dreams are experiences. Even dreamless sleep involves some dim, diffuse experience. Hell, there may even be something that it feels like to be in a coma. The point is: consciousness doesn’t require being awake.

You don’t need an inner monologue. That voice in your head that “feels like you” is different from consciousness. It’s just one thing you can be conscious of, one element in experience. Plenty of people don’t have an inner monologue, and they’re doing fine (presumably).

You don’t need to know you’re conscious. You can be absorbed in an activity and still be having an experience. You can have no memories of an experience entirely and it still happened.

You don’t need to pass the mirror test. Recognizing yourself in a mirror is a neat trick that requires certain cognitive abilities. Babies can’t do it. Many animals can’t do it. They’re still conscious (probably).

Consciousness is not necessarily created by the brain. Most people assume the brain generates consciousness, like a lamp generates light. But this is an assumption, not a proven fact. We know the brain correlates with consciousness, because changes in the brain are linked to changes in experience. But jellyfish don’t have brains, and that doesn’t mean they don’t have an experience. Maybe the brain is more like a receiver or a filter than a generator. Maybe not. The point is: we don’t actually know.

Consciousness is not the same as information processing. When you see the color red, there’s a physical story: photons at 700nm hit your retina, trigger photoreceptors, send signals down the optic nerve, activate patterns in visual cortex. That’s the information processing. But that’s not the redness. The redness — the fact that you’re seeing the color red — is something else. For example, you can experience red in a dream. Your eyes are closed. No photons are involved. Yet there it is, red, sometimes seeming even more real than in waking life. The experience can happen without the physical process that usually causes it, so the experience isn’t identical to the process. Another classic thought experiment here: is your red the same as my red? The same photons may hit our retinas, trigger similar neural pathways, and we both say "red." But on our “screens of consciousness”, my experience of red is what you'd call blue! Or something you’ve never experienced at all! There’s no way to know.

The “atoms” of experience, the felt quality of seeing the redness of red, or the pain of touching a hot stove, are called qualia.

The problem of other minds

Now that we know what we mean by consciousness, an uncomfortable fact arises: we have no way to verify whether anything other than ourselves is conscious. Like, I literally may be the only being with an inner experience while all of you are just faking it.

Saying that you are conscious is not enough. Imagine a sophisticated humanoid robot. It has cameras for eyes, microphones for ears, advanced AI software to process inputs and generate responses. It holds conversations, expresses emotions, claims to have an experience. Is it conscious?

Maybe, maybe not. You just can’t tell from the outside; you can’t access its inner experience (if there’s any). You can only observe its behavior, and behavior doesn’t prove consciousness. A sufficiently advanced system could produce all the right behaviors with nothing going on inside (look at LLMs fooling everyone these past years).

This is the problem of other minds. It applies to robots, to animals, to everyone around you…

The hard problem

The problem at the core of it all is: Why is there any experience at all?

Suppose we fully explain every mechanism in the brain: every neuron, synapse, chemical signal... We can predict its behavior perfectly. We’ve basically “solved” the brain. Have we explained consciousness? Most likely not, because we still haven’t explained why all that machinery feels like something from the inside. We’ve explained what the brain does, but not why there’s a “what it’s like” to being a brain.

God (or evolution, pick your favorite) could have set up everything exactly the same way, the exact same universe with all its laws, atoms, and inhabitants, except… without anything to actually feel it.

This is the “hard problem of consciousness”.

Other problems

There are many other “problems” we face when discussing consciousness.

The explanatory gap: Related to the hard problem. If consciousness is “physical”, why do certain brain states produce certain experiences? Why does dopamine release feel good? What’s the link between them? It sometimes seems completely arbitrary.

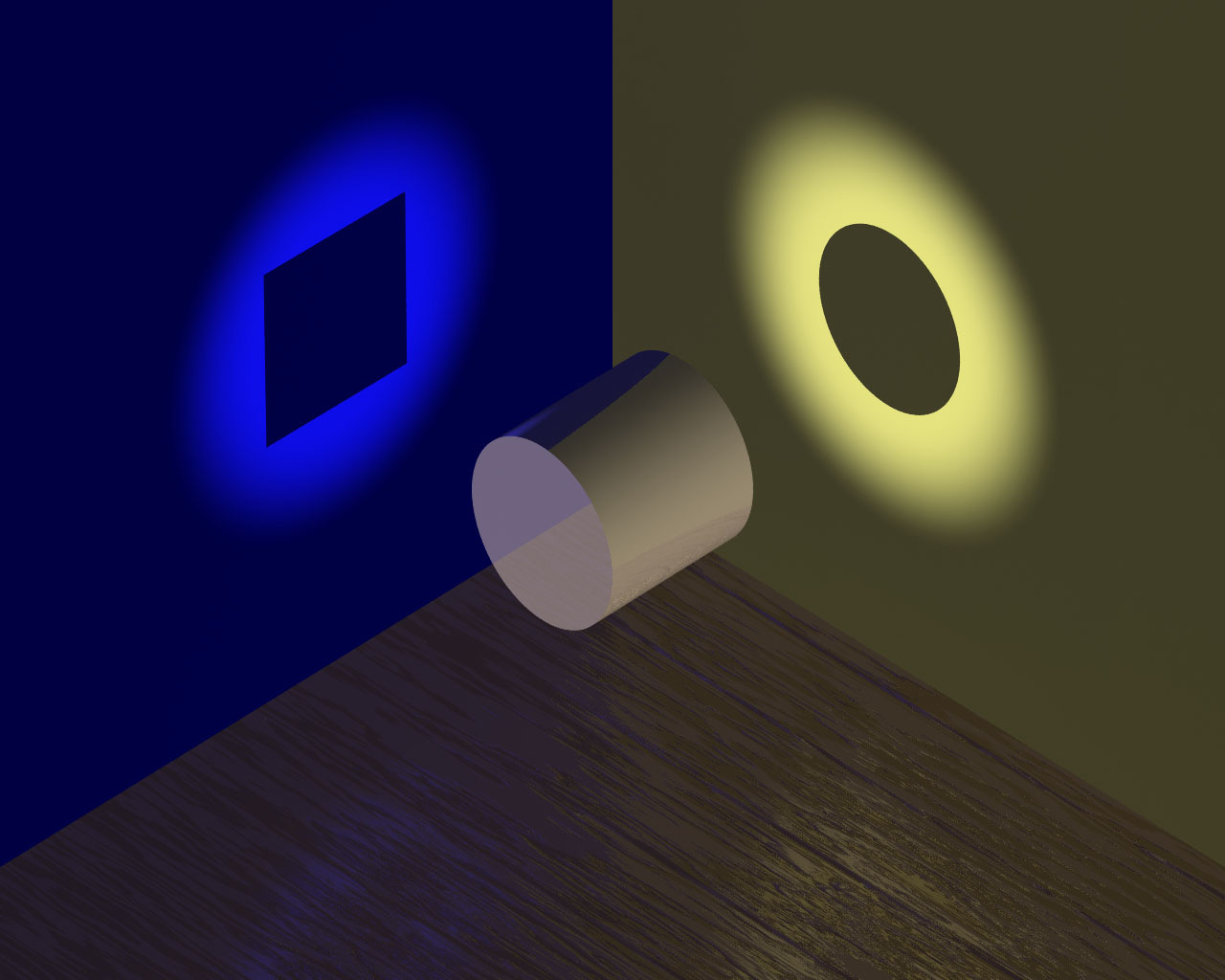

The binding problem: Right now, your experience is unified. You see the light of your screen and its shape and hear the background sounds and feel the chair under you, all as one coherent experience. But the brain processes these features in different regions. Color in the occipital lobe, sound in the temporal lobe, somatic sensations in the parietal lobe, etc. How do they come together into a single unified experience? What does the binding, the “combination” of these different outputs?

The boundary problem: Related to the binding problem. What determines the “limits” of your experience? Why does your consciousness stop at your skull? Why don’t you merge with me when we’re in the same room? What determines where one consciousness ends and another begins?

The palette problem: Why does red look like that? Why does pain feel bad rather than purple? What is the total range of qualia possible to experience, and why don’t we have access to all of them?

The causal efficacy problem: Does consciousness do anything? Can it act on the physical world? Or is the physical world only ruled by “physical” cause and effect? In other words, is consciousness epiphenomenal (it just happen to be there, there is an experience but it has no power)?

The vertiginous question: Why am I this consciousness and not another one? Of all the conscious beings that exist, why is my experience coming from here? Why am I Pierre and not someone else?

A map of theories

There are many theories that try to explain consciousness; here’s a brief tour. Apologies in advance if I misrepresent some of the arguments.

1. Illusionism

Consciousness as we think of it doesn’t exist. It’s an… illusion.

Illusionists say that we think we have rich inner experiences, but we’re mistaken: there’s just information processing. The brain tells itself it’s having experiences, but there’s no actual experience behind this report.

This is elegant because it dissolves almost all the problems. If consciousness isn’t a thing, we don’t need to explain how it arises or why it feels the way it does. Physics become self-sufficient.

But the fact that there is an experience happening right now feels like the most fundamental thing, the one thing I can say with absolute certainty. Also, what exactly is the difference between having an experience and seeming to have an experience? If there’s an impression of redness, isn’t that impression itself an experience? Illusionism is puzzling.

2. Physicalism

Consciousness is physical. It’s just what brains do.Your experience of red is a certain pattern of neurons firing. We feel like there’s something extra because brains are complicated and we don’t fully understand them yet, but it’s all just matter in motion.

This seems promising because that’s how a lot of science has worked over time. “Life” seemed mysterious until we understood biochemistry. “Heat” seemed mysterious until we realized it's just molecules moving. Maybe “consciousness” is like that, it feels mysterious now, but one day we'll see it was just neurons all along.

The issue is: when we reduced heat to molecular motion, for example, nothing was left out. But with consciousness, there is still something missing. Why does this neural pattern feel like anything? Why does it feel like this?

3. Functionalism

Functionalism shifts the focus from the stuff to the pattern.

What matters isn’t that your brain is made of neurons but how information flows through it. Consciousness is a certain kind of organization, a certain way of processing information. The substrate (= the “material”) is irrelevant.

For example, according to functionalists, if a computer processed information the same way your brain does, it would be conscious too. Consciousness is what the system does, not what it’s made of. This means that ChatGPT could be conscious past a certain threshold of complexity.

But, again, there’s an issue. You could, in principle, simulate a large language model by hand. A person sitting in a room with an enormous instruction manual, looking up rules, writing outputs token by token. Is this person conscious of what they’re processing? Most people’s intuition says no. They’re just shuffling symbols (see also the Chinese room). But if that’s right, why would running the same process faster, on silicon, create consciousness? What changes?

4. Emergentism

Consciousness is real, but it’s not fundamental; it emerges from physical complexity.

The idea is: get enough neurons, organize them the right way, and consciousness appears. It’s not directly in the components, a single neuron isn’t conscious, for example, but it arises from the whole. Like how a single water molecule isn't wet, but a trillion of them together are.

This feels quite reasonable. It takes consciousness seriously without adding anything too mysterious to physics. Consciousness is just what happens when matter gets complex enough.

The problem is:

You start with atoms → no consciousness.

You build molecules → still nothing.

You assemble neurons → nothing.

You connect a thousand neurons → nothing.

A million → nothing.

A billion → nothing.

And then at some point → something?

Is there a magic threshold? You add one extra neuron and boom! there is experience? That seems weird. And even if it’s gradual, what does “half-conscious” even mean? You either have an experience or you don’t, right?

Also, “wetness” is just a word for how water molecules behave together, it’s not a new thing that appears. But with emergence, consciousness is supposed to be genuinely new from an arrangement of neurons. This raises the question: why this arrangement of neurons? Why not one slightly different? What’s the rule? If there’s no rule, we’ve just labeled the mystery “emergence” without explaining it.

5. Panpsychism

If you can’t explain how experience arises from non-experience, maybe it never does. Consciousness is fundamental, it is a raw fact of the universe, like mass or charge. This means that even an electron has some kind of proto-experience: not thoughts or feelings, just... something it’s like to be an electron. Your complex human consciousness isn’t created from nothing; it’s built from many simpler building blocks.

Panpsychism avoids the hard problem of emergence. We don’t have to do a magical jump from non-conscious to conscious. Experience is always there; it just gets more complex as organisms get more organized.

But remember the binding problem. If electrons have micro-experiences, how do trillions of them add up to your unified experience? You feel like one thing, not many trillions. How do little experiences merge into big experiences?

And there was also the boundary problem: why does our consciousness “stop” where it does? Why aren’t we aware of everything in the universe?

These feel slightly more solvable than the emergence problem, but there’s still a lot to explain.

6. Dual-Aspect Monism

Closely related to panpsychism (debatable if it should be classified under or be separate). The core idea is similar: experience is fundamental, not emergent, but the framing is slightly different.

While panpsychism says experience is a property things have, dual-aspect monism says experience is what things are, from the inside. There’s one reality, and it has two “sides”. Physics describes the outside: how things behave, interact, etc. Experience is the inside: what it’s like to be these things.

The pros and cons of this theory are pretty much the same as for panpsychism. The small advantage here is that it clarifies why the hard problem might be unanswerable from physics alone. Physics and experience are just two aspects of the same thing. So “why does consciousness exist?” reduces to “why does anything exist?”, which is still as hard or even harder, but at least we only have one question.

7. Idealism

What if we have it backwards? What if, instead of consciousness emerging from matter, matter emerges from consciousness?

Idealists says: what we call the “physical world” is actually a structure within consciousness. Matter is what experience looks like when you measure it, or how experiences relate to each other.

This is a bit trippy, but I think a decent way to explain this is to think about dreams. In a dream, there are objects, spaces, other people... But it’s all made of “mind”. There is no actual matter. It’s just experience structured in a way that feels like a world.

So idealism thinks waking life is like that too. It’s not fake, but the underlying nature of the universe is experiential, not material.

The challenge: why does the physical world seem so stable and independent? If everything is mind, why can't I think the wall away (like in a lucid dream)? Why does gravity work whether I believe in it or not? Why do we all seem to share the same world instead of each living in our own private dreamscape?

Idealists have answers to those but they all feel a little hand-wavy.

Where do we stand?

As you can notice, none of the theories feels perfect and they all may be far from the truth. However, since this my blog, I’ll tell you what I believe. Or rather, what the Qualia Research Institute made me believe, because, let’s be honest, I’m not smart enough to come up with this on my own.

Here’s the reasoning:

Starting with experience makes more sense than creating it from nothing. The hard problem is hard because we’re trying to derive experience from non-sentient matter. But if experience is a fundamental aspect of reality, then there’s no magical moment where the “lights turn on” (since they were always on).

But as we said, we have to explain the binding problem. If experience is fundamental and everywhere, why are you one unified consciousness rather than billions of tiny ones? One possible answer involves the electromagnetic field.

Indeed, every neuron firing creates electromagnetic effects. These combine into a single field that extends throughout your whole brain. And unlike neurons, which are separate objects, this field is continuous and unified.

You may see where I’m going with this: if consciousness is somehow associated with this field, binding comes automatically. You don’t have to aggregate trillions of tiny experiences. You’re one field, having one experience.

One problem remains, though: we still need boundaries. Why don’t two brains next to each other merge into one experience?

Think of a balloon. You can twist to create separate sections. There’s no wall between them, it’s still one continuous piece of rubber. But the twists create boundaries. Each section is now its own enclosed space.

Consciousness could work similarly. A “subject” (or a “point of view”) exists where the field loops back on itself to create a “closed structure”. Your brain and mine don’t merge because our fields, though close to each other, aren’t connected, like two sections of a balloon.

This is the topological solution to the boundary problem. Topology is the study of geometrical properties and spatial relations unaffected by the continuous change of shape or size of figures.

Why consciousness matters

Consciousness problems and theories are fascinating philosophical puzzles, but they can also feel abstract and just not very useful.

Yet, they can have an extremely significant ethical impact:

Artificial intelligence: We’re building increasingly sophisticated AI. If consciousness depends on specific physical structures (like EM fields with certain topology), then most current AI isn’t conscious and won’t be regardless of capabilities. But if consciousness depends on information processing, we might be building conscious beings right now, and should probably think about their moral status. We may be inflicting significant suffering on these beings without us realizing it.

Animal welfare: Which animals are conscious? This is, again, a question that depends on what generates consciousness. But it also has massive ethical implications. If all beings have an experience and can feel pain and suffering, we should think about it for a minute. Maybe a lot of suffering is concentrated in tiny animals like shrimps.

In addition, learning what consciousness really is and how it works could unlock a lot of applications in mental health and well-being in general. Hell, it might even inform us on what truly happens after we die.

Amazing

Re idealism this assumes that idealism is some species of what Berkeley thought (but without a God to keep things consistent) but you could just as well go to say, Kant's transcendental idealism which if anything was trying to rigorously answer something like "why does gravity work whether I believe in it or not" and so on